Dreams That Money Can Buy

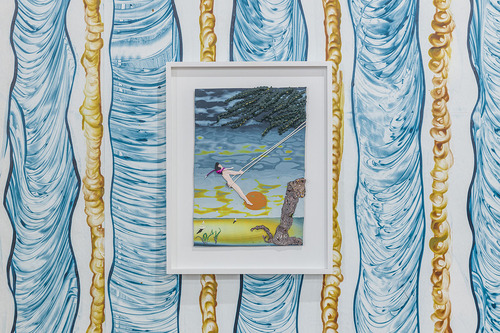

1/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

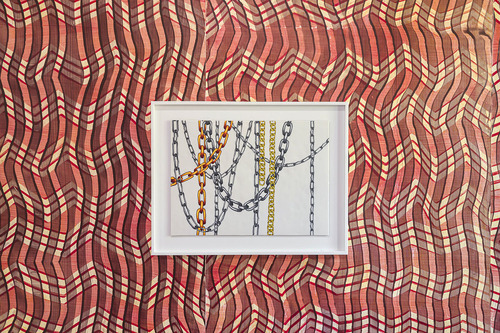

2/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

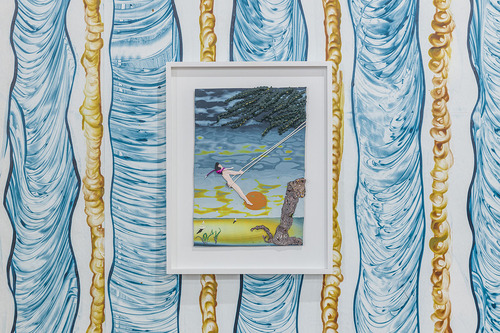

3/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

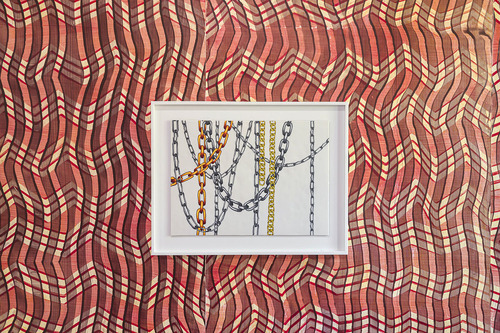

4/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

5/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

6/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

7/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

8/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

Exhibition 1. September 2023 - 4. August 2024

Philip Wiegard

(with Kasi Althaus, Elena Peters Arnolds, Beehave, Baltazar Castor, Joe Caviani, Gabriel Cazzato, Gaia Coletti, Cordialiyours, Cyprus Polymer Clay Association, Kathy Hepburn, ikandiclay, Kids' Factory, Jutta Klingel, Laura L. LePere, Aude Levère, Layl McDill, Gaia Micalizzi, Gaia Sofia Natali, Mara Palata, Andrea Victoria Paradiso, Denise Pinnell, Mina Pirschel, Melissa Redner, Christin Rothe, Kim Snowden, Suzie Sullivan, Amy Sutryn, Rosana VanHorn)

Schloss Gandegg

Via Piganò 19

30957 Eppan/Appiano, Italy

OPEN HOURS

Exhibition 07.04 - 04.08.2024

Always open on the first Sunday of the month from 12:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.

Exhibition open by appointment +39 320 426 8178

The exhibition Dreams That Money Can Buy is the first major show of Berlin-based artist Philip Wiegard in South Tyrol. Works spanning from the last 15 years will provide deep insight into his practice of collaborative work, and the blurred boundaries between labor and artistic practice.

On this occasion, many new works will be shown for the first time and partly produced in South Tyrol. During the Kids’ Factory workshop at Schloss Gandegg a series of hand-painted wallpapers will be produced by children between the ages 8-14. The wallpaper is part of the exhibition and spans over the second floor of the castle. The children, holding the role of the artist assistants, therefore contribute significantly to the success of the exhibition. Wiegard’s artistic practice pervades questions about authorship, production processes, and working conditions by paying an hourly wage to the participating kids.

The video installation Dreams That Money Can Buy will premiere in Wiegard’s exhibition. It features a cast of professional child actors, who interpret Loïe Fuller’s serpentine dance, while the soundtrack is played by the artist himself on the piano. The performance is an artistic examination of his own childhood dreams of success and career and deals with ideas such as virtuosity, expression, and talent.

A new series of polymer clay mosaics will be on display. Following principles of collective working, he incorporates pieces from other artists of the polymer clay community which he receives in exchange. Wiegard is an active part of this community which is based on social media channels such as youtube and tiktok. Through tutorials he teaches and has been taught in various techniques of polymer art.

Exhibtion Text by Wolfgang Ullrich:

Philip Wiegard’s Ethic of Cooperation

It goes without saying that more work goes into art than what can be seen as a finished piece or action in an exhibition space. Interviews, for one, are part of it, as are public appearances, project developments, and financing strategies. Today, though, not even those are enough. What has changed is the role artists play and their understanding of what they do. Many of them no longer lay claim to any elevated special status, instead building extensive networks and drawing on others’ expertise in diverse fields. The result, however, is that creative processes are more complicated: artists must renounce the gesture of positively absolute power, of complete independence, and instead show consideration for all those with whom they interact. And the more firmly they believe that everyone involved is essentially equal, the more an idea of fairness becomes. Artistic work then consists in no small part in an ongoing negotiation of what all sides perceive as fair. What’s needed is an ethic of cooperation.

Such an ethic is central to Philip Wiegard’s work. It forms the foundation of his projects, and it doesn’t play out only behind the scenes, either. By picking up on forms of work associated with craftsmanship and recreational creative pursuits, Wiegard aligns himself with a tradition of appropriation art, and so the contributions of others are always an explicit concern in his art. For example, he will make paste-paper wallpapers—a premodern and almost extinct technique—in workshops with children, many of whom take special pleasure in the repetitive procedures of pattern-making. Yet the fact that he pays

them for their work should be seen not only as a token of his appreciation, it also raises the critical question of whether the revival of an obsolete technique brings back another thing of the past as well: child labor. And are even children now altogether subject to the logic of economics?

Wiegard, that is to say, wants to start a debate on what might come closest to an idea of fairness. Instead of remunerating the children, perhaps it might be fairer to list their names in exhibitions showcasing the wallpapers, honoring them as proud collaborators? Or might it not be better if, in exchange for their labor, he made room in the workshops for their own unguided experimentation with the materials? By raising questions like these in each new project and arriving at fresh answers rather than compensating the participants in accordance with a predetermined scheme, he sharpens the focus on the subject of fairness. Unlike, say, Santiago Sierra, whose actions are limited to a critique of exploitative forms of compensation, turning the spotlight on grievances yet also reproducing the exploitation in ways that are not unproblematic, Philip Wiegard delineates specific standards of collaboration.

The concern with fairness extends beyond questions of acknowledgment and remuneration, as his work in FIMO, a modeling clay that’s popular with various hobbyist scenes, illustrates. By using a material that has been as far outside the hallowed halls of fine art as one can imagine and that, in fact, typically features in decorative handicrafts, Wiegard is dealing with artifacts made by people who (just like children) rank way below artists in status, making it all the more difficult to devise a practice that achieves balance and equality.

When artists like Roy Lichtenstein or Richard Prince tapped aesthetics similarly distant from fine art—the work of cartoonists in one case, the biker scene in the other—for their appropriation art, they were still intent on that absolutist artistic gesture, so much so that they did not bother about fairly sharing the rewards with their unwitting sources. They did not even ask whether they were free to use something; faced with claims that they had violated other creators’ rights, they refused to recognize them in any way, apparently seeing everything outside and below art as fair game available for them do with as they saw fit.

If that approach is increasingly seen and condemned as arrogant and classist, Philip Wiegard’s practice is apt to underscore the point. He integrates the major or minor stars of the FIMO scene whose motifs he finds interesting into his creative processes from the outset; he consults with them to define the terms of his use of their works, proposes how to share any proceeds with them, and even concludes loan agreements when he wants to exhibit their objects. But that’s not all. It’s also important to Wiegard not to be perceived as a kind of conquistador of the clay-modeling scene, someone who autocratically decides what he likes, whom he will put on the map, and what he will consign to oblivion. That’s why he started working with FIMO himself; he watched tutorials to learn from the pros and, having become a pro himself, produced tutorials of his own in which he demonstrates his techniques and tricks in handling the material. Thanks to YouTube and TikTok, where Wiegard posts his tutorials, he has emerged as a star clay artist in his own right and a member of the scene in good standing—not a stranger who is distrusted or possibly suspected of sinister interests.

And by finding a way to share his knowledge about the modeling clay rather than simply appropriating FIMO artifacts, he has opened up additional avenues of creative engagement. The work “Sunset Suites” (2021), for example, consists of a series of FIMO pictures that clay artists made based on one of Wiegard’s tutorials and that reveal their creativity in how they adapt the setting-sun motif they have learned from him. In exhibiting these pictures, Wiegard once again switches roles: the teacher becomes a curator who draws the art world’s attention to the creators. But where the appropriation art tradition would brand their works as exotica, inviting the fine-art community to savor its putatively superior taste, he does everything in his power to make viewers appreciate their formal qualities and embrace them as an enriching contribution to contemporary art.

For evidence of how serious Wiegard is about this undertaking, consider the fact that he struck up a collaboration with people from the clay modeling community for several of his FIMO pictures. Their motifs as well as effects he learned in their workshops are an equal-ranking and sometimes even visually dominant part of the pictures, and their authorship is specifically mentioned in the notes accompanying the works. In several instances, the compositions are designed to set off their contributions from the remaining areas, arguably suggesting that they’re being staged not unlike the donor figures in medieval paintings: as elements of a different reality without which the picture would not exist and which is therefore acknowledged within it.

These works, then, not only represent an impressive culmination of Philip Wiegard’s ethic of cooperation, they manifest it in their physical facture. And the more that ethic extends beyond a mere procedural concern that figures in the background of the work of art, the more clearly it contrasts with the inconsiderateness that was often a hallmark of modernism. Wiegard exemplifies a new kind of artist, one who has taken the insight to heart that he must give back to the people or scenes from whom or which he takes something. In this sense, fairness also implies sustainability: indeed, the ethic of cooperation is inspired by an ecological thinking in cycles and interconnected wholes. Being an artist today means establishing such ecology in an effort to overcome inequitable and unfair structures and practices.

Translated by Gerrit Jackson

Ausstellung

Ausstellung "Dreams That Money Can Buy" by Philip Wiegard

(mit Kasi Althaus, Elena Peters Arnolds, Beehave, Baltazar Castor, Joe Caviani, Gabriel Cazzato, Gaia Coletti, Cordialiyours, Cyprus Polymer Clay Association, Kathy Hepburn, ikandiclay, Kids' Factory, Jutta Klingel, Laura L. LePere, Aude Levère, Layl McDill, Gaia Micalizzi, Gaia Sofia Natali, Mara Palata, Andrea Victoria Paradiso, Denise Pinnell, Mina Pirschel, Melissa Redner, Christin Rothe, Kim Snowden, Suzie Sullivan, Amy Sutryn, Rosana VanHorn)

Schloss Gandegg

Via Pigano 19

30957 Eppan/Appiano

ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN

Ausstellung 07.04 - 04.08.2024

Immer geöffnet am ersten Sonntag des Monats von 12:00 bis 18:00 Uhr.

Ausstellung nach Vereinbarung geöffnet +39 320 426 8178

Die Ausstellung Dreams That Money Can Buy ist die erste große Ausstellung des in Berlin lebenden Künstlers Philip Wiegard in Südtirol. Werke aus den letzten 15 Jahren geben einen tiefen Einblick in seine Praxis der Zusammenarbeit und in die verschwimmenden Grenzen zwischen Arbeit und künstlerischer Praxis.

Bei dieser Gelegenheit werden viele neue Werke zum ersten Mal gezeigt, die teilweise in Südtirol entstanden sind. Im Rahmen des Workshops Kids' Factory auf Schloss Gandegg wird eine Serie von handbemalten Tapeten von Kindern im Alter von 8-14 Jahren hergestellt.

Die Tapeten sind Teil der Ausstellung und erstrecken sich über den zweiten Stock des Schlosses. Die Kinder, die die Rolle der Künstlerassistenten innehaben, tragen somit wesentlich zum Erfolg der Ausstellung bei.

Wiegards künstlerische Praxis durchdringt Fragen nach Autorenschaft, Produktionsprozessen und Arbeitsbedingungen, indem sie den beteiligten Kindern einen Stundenlohn zahlt.

Die Videoinstallation Dreams That Money Can Buy wird in Wiegards Ausstellung uraufgeführt. Professionelle Kinderschauspieler wurden gecastet und engagiert den Serpentinentanz von Loïe Fuller zu interpretieren, während der Soundtrack vom Künstler selbst auf dem Klavier gespielt wird. Die Performance ist eine künstlerische Auseinandersetzung mit seinen eigenen Erfolgs- und Karriereträumen aus der Kindheit und beschäftigt sich mit Ideen wie Virtuosität, Ausdruck und Talent.

Eine neue Serie von Mosaiken aus Polymer-Ton wird zu sehen sein. Nach den Prinzipien des kollektiven Arbeitens integriert er Stücke von anderen Künstlern aus der Gemeinschaft der Polymer Clay-Künstler, die er im Austausch erhält. Wiegard ist ein aktiver Teil dieser Gemeinschaft, die sich auf Social-Media-Kanäle wie youtube und tiktok stützt. In Tutorials unterrichtet er und wurde in verschiedenen Techniken der Polymer Art unterrichtet.

Ausstellungstext:

Wolfgang Ullrich

Philip Wiegards Ethik des Kooperierens

Dass künstlerische Arbeit mehr umfasst als das, was in einem Ausstellungsraum als Werk oder Aktion zu sehen ist, versteht sich von selbst. Genauso gehören etwa Interviews, Auftritte, Projektentwicklungen und Finanzierungsstrategien dazu. Doch heute genügt auch das nicht. Vielmehr haben sich Selbstverständnis und Rolle von Künstler:innen geändert. Viele beanspruchen keinen erhabenen Sonderstatus mehr, sind dafür gut vernetzt und nutzen gerne das Know-how anderer Bereiche. Das aber macht Werkprozesse komplizierter, denn statt mit einem geradezu absolutistischen Gestus, im Bewusstsein völliger Unabhängigkeit auftreten zu können, hat man dann als Künstler:in Rücksicht zu nehmen auf jene, mit denen man interagiert. Und je überzeugter man davon ist, dass alle Beteiligten grundsätzlich gleichberechtigt sind, desto wichtiger wird eine Idee von Fairness. Künstlerische Arbeit besteht dann nicht zuletzt darin, immer wieder auszuhandeln, was für alle fair ist. Es geht um eine Ethik des Kooperierens.

Für Philip Wiegards Arbeit ist eine solche Ethik zentral. Sie bildet die Grundlage seiner Projekte und spielt sich auch nicht nur im Backstagebereich ab. Denn da Wiegard Werkformen aufgreift, die mit Handwerk und Hobby assoziiert sind, sich also in eine Tradition der ‚Appropriation Art’ stellt, sind die Beiträge anderer Menschen immer ausdrücklich Gegenstand seiner Kunst. Tapeten aus Kleisterpapieren – dies eine vormoderne, fast ausgestorbene Technik – erstellt er etwa in Workshops mit Kindern, die an den repetitiven Abläufen der Mustererzeugung oft besonderen Spaß haben. Dass er sie für ihre Tätigkeit bezahlt, ist aber nicht nur als Ausdruck von Wertschätzung zu deuten, sondern soll zugleich die kritische Frage aufwerfen, ob mit der Rückkehr einer alten Technik auch die an sich überwundene Kinderarbeit zurückkehrt. Und werden jetzt sogar schon Kinder gänzlich der Logik der Ökonomie unterworfen?

Wiegard will also eine Debatte darüber eröffnen, was einer Idee von Fairness am ehesten entsprechen könnte. Vielleicht wäre es ja fairer, die Kinder nicht zu entlohnen, dafür aber bei Ausstellungen mit den Kleistertapeten ihre Namen aufzuführen und sie so als stolze Mitwirkende zu würdigen? Oder wäre es nicht besser, er würde ihnen für ihren Einsatz in den Workshops auch Spielraum für freie Experimente mit den Materialien lassen? Indem er solche Fragen von Projekt zu Projekt neu stellt und auch immer wieder neu beantwortet, also kein festes Schema hat, mit dem er Beteiligte abfindet, macht er das Thema ‚Fairness’ umso präsenter. Anders als etwa Santiago Sierra, der sich in seinen Aktionen auf Kritik an ausbeutenden Formen der Entlohnung beschränkt, indem er Missstände sichtbar macht, die Ausbeutung dabei aber auch – nicht unproblematisch – reproduziert, gestaltet Philip Wiegand eigene Standards für Zusammenarbeit.

Dass es ihm dabei keineswegs nur um Fragen der Honorierung geht, wird an seinen Arbeiten mit der in verschiedenen Hobbyszenen beliebten Modelliermasse FIMO deutlich. Sofern Wiegard hier ein Material verwendet, das bisher denkbar weit von jeglicher ‚Kunstwürde’ entfernt war, ja mit dem üblicherweise Kunstgewerbliches produziert wird, hat er es mit Artefakten von Leuten zu tun, die traditionell (genauso wie Kinder) einen viel niedrigeren Status als Künstler:innen innehaben. Umso schwerer ist es, ein faires, auf Ausgleich und Gleichberechtigung bedachtes Handeln zu realisieren.

Künstler wie Roy Lichtenstein oder Richard Prince, die sich für ihre ‚Appropriation Art’ bei ähnlich kunstfernen Ästhetiken etwa von Comic-Zeichnern oder aus der Motorrad-Szene bedienten, waren noch zu stark auf jenen absolutistischen Kunstgestus ausgerichtet, um sich auch nur Gedanken über deren gerechte Beteiligung zu machen. Sie fragten nicht einmal, ob sie etwas verwenden durften, und selbst wenn die Betroffenen im Nachhinein Ansprüche anmeldeten, verweigerten sie jegliche Anerkennung, ja sahen in allem außer- und unterhalb der Kunst offenbar Freiwild, über das sie beliebig verfügen durften.

Dazu, dass ein solches Verhalten mittlerweile zunehmend als Arroganz und Klassismus (dis)qualifiziert wird, dürfte Philip Wiegards Arbeitsweise weiter beitragen. So integriert er die größeren oder kleineren Stars der FIMO-Community, deren Motive er interessant findet, von Anfang an in seine Werkprozesse; er klärt, unter welchen Bedingungen er ihre Arbeit nutzen kann, macht Vorschläge, wie er sie an möglichen Einnahmen beteiligt, und schließt sogar Leihverträge, wenn er ihre Objekte ausstellen will. Damit aber nicht genug. Vielmehr ist es Wiegard auch wichtig, dass er nicht wie ein Eroberer in der Szene der Clayer wahrgenommen wird, der selbstherrlich entscheidet, was ihm gefällt, wen er pusht und was er links liegen lässt. Deshalb begann er, selbst mit FIMO zu arbeiten; er schaute sich Tutorials an, um von den Profis zu lernen, und bietet, seit auch er Profi ist, seinerseits Tutorials an, in denen er seine Techniken und Tricks im Umgang mit dem Material vorführt. Dank YouTube und TikTok, wo Wiegard seine Tutorials postet, ist er inzwischen selbst ein Star unter den Clayern: voll in die Szene integriert – kein Fremdling, den man beargwöhnt oder dem man sinistre Interessen unterstellen könnte.

Dass er Artefakte aus FIMO nicht nur übernimmt, sondern sein Wissen über die Modelliermasse weitergeben kann, eröffnet ihm noch weitere Möglichkeiten. So besteht die Arbeit „Sunset Suites“ (2021) aus einer Serie von FIMO-Bildern, die Clayer nach einem Tutorial von Wiegard angefertigt haben und in denen sich zeigt, wie kreativ sie das von ihm gelernte Motiv einer untergehenden Sonne einsetzen. Wenn Wiegard diese Bilder ausstellt, wechselt er nochmals die Rolle und wird vom Lehrer zum Kurator, der den Urheber:innen Aufmerksamkeit in der Kunstwelt verschafft. Statt ihren Arbeiten dort aber, wie in der Tradition der ‚Appropriation Art’ üblich, nur einen Exoten-Status zu verpassen, der es dem Kunstpublikum erlaubt, die vermeintliche eigene Geschmacksüberlegenheit zu genießen, tut er alles dafür, dass sie in ihren formalen Qualitäten geschätzt, als Bereicherung für die zeitgenössische Kunst empfunden werden.

Wie ernst Wiegard das nimmt, beweist er nicht zuletzt damit, dass er für einige seiner FIMO-Bilder eine Kooperation mit Clayern aus der Community eingegangen ist. Deren Motive oder auch Effekte, die er in ihren Workshops gelernt hat, sind gleichberechtigter, manchmal sogar visuell dominanter Teil der Bilder, ihre Urheberschaft ist in den Werkangaben eigens vermerkt. In einigen Fällen, in denen er ihre Parts kompositionell klar von den übrigen Partien abgrenzt, könnte man sogar darauf kommen, dass jene ähnlich wie Stifterfiguren in mittelalterlichen Gemälden in Szene gesetzt sind: als Elemente einer anderen Wirklichkeit, die das Bild aber erst ermöglichen und nun in ihm gewürdigt werden.

Auf diese Weise gelangt Philip Wiegards Ethik des Kooperierens nicht nur zu einem eindrucksvollen Höhepunkt, sondern manifestiert sich auch in den Werken selbst. Und je mehr diese Ethik darüber hinausgeht, nur eine prozedurale Angelegenheit im Hintergrund der künstlerischen Arbeit zu sein, desto klarer steht sie im Kontrast zur oft rücksichtslosen Moderne. Exemplarisch repräsentiert Wiegard einen neuen Künstlertypus, der von der Einsicht geprägt ist, dass man den Menschen oder Bereichen, von denen man etwas bezieht, etwas zurückzugeben hat. Fairness meint damit zugleich Nachhaltigkeit, ja die Ethik des Kooperierens folgt einem ökologischen Denken in Kreisläufen und Zusammenhängen. Heute Künstler:in zu sein, heißt, diese zu etablieren und auf diese Weise einseitige und ungerechte Verhältnisse zu überwinden.

Esposizione

Philip Wiegard

(con Kasi Althaus, Elena Peters Arnolds, Beehave, Baltazar Castor, Joe Caviani, Gabriel Cazzato, Gaia Coletti, Cordialiyours, Cyprus Polymer Clay Association, Kathy Hepburn, ikandiclay, Kids' Factory, Jutta Klingel, Laura L. LePere, Aude Levère, Layl McDill, Gaia Micalizzi, Gaia Sofia Natali, Mara Palata, Andrea Victoria Paradiso, Denise Pinnell, Mina Pirschel, Melissa Redner, Christin Rothe, Kim Snowden, Suzie Sullivan, Amy Sutryn, Rosana VanHorn)

Castel Ganda

Via Pigano, 19 30957 Appiano

ORARI DI APERTURA

Mostra 07.04 - 04.08.2024

Sempre aperto la prima domenica del mese dalle 12:00 alle 18:00.

Mostra aperta su appuntamento +39 320 426 8178

La mostra Dreams That Money Can Buy è la prima grande esposizione dell'artista berlinese Philip Wiegard in Alto Adige. Le opere esposte, realizzate negli ultimi 15 anni, offriranno una visione approfondita della sua pratica collaborativa e dei labili confini tra attività lavorativa e pratica artistica.

La mostra presenta molte opere nuove, in parte prodotte in Alto Adige. Durante il laboratorio Kids' Factory presso Castel Ganda, una serie di carte da parati dipinte a mano sarà realizzata da bambini/e di età compresa tra gli 8 e i 14 anni. La carta da parati farà parte della mostra e verrà esposta nel secondo piano del castello. I bambini/e, che ricoprono il ruolo di assistenti dell'artista, contribuiscono quindi in modo significativo al successo della mostra. Philip Wiegard, nella sua pratica artistica collaborativa, pagando una retribuzione oraria ai bambini partecipanti si interroga sulla nozione di autorialità, sui processi di produzione e sulle condizioni di lavoro,.

All’interno della mostra, verrà presentata in anteprima l’installazione video Dreams That Money Can Buy. L’installazione video è composta da un cast di bambini attori professionisti che interpretano la danza serpentina di Loïe Fuller, mentre la colonna sonora è suonata dall'artista stesso al pianoforte. La performance è una rielaborazione dei suoi sogni infantili di successo e di carriera e tratta idee come il virtuosismo, l'espressione e il talento.

Insieme alla carta da parati e l’installazione video, verrà esposta una nuova serie di mosaici in argilla polimerica. Seguendo i principi del lavoro collettivo, Wiegard incorpora pezzi di altri artisti della comunità dell'argilla polimerica che ha ricevuto in cambio di lezioni. L’artista è parte attiva di questa comunità che si sviluppa su canali di social media come youtube e tiktok. Attraverso i tutorial insegna e ha potuto imparare svariate tecniche di lavorazione dell'argilla polimerica.

Testo della mostra:

Wolfgang Ullrich

Philip Wiegard e l’etica della cooperazione

Va da sé che il lavoro artistico non si limita a ciò che si può vedere in uno spazio espositivo come opera o azione. Esso comprende anche interviste, performance, lo sviluppo di progetti nonché le strategie di finanziamento. Tuttavia, oggi anche questo non è più sufficiente. Sono piuttosto cambiati l'immagine di sé e il ruolo degli artisti. Molti non rivendicano più un elevato status sociale, ma sono ben interconnessi tra loro e amano utilizzare il know-how di altri settori. Questo, però, rende più complicati i processi di lavoro, perché invece di poter apparire con un gesto quasi assolutistico, nella consapevolezza di una completa indipendenza, come artista si deve poi tenere conto di coloro con cui si interagisce. E quanto più si è convinti che tutti i partecipanti siano fondamentalmente uguali, tanto più diventa importante un'idea di equità. Ma il lavoro artistico consiste anche nel negoziare continuamente ciò che è giusto per tutti. Si tratta quindi di un'etica della cooperazione.

Per il lavoro di Philip Wiegard questo tipo di etica è un punto centrale. Essa non si svolge solo dietro le quinte, ma costituisce la base dei suoi progetti. Poiché Wiegard adotta forme di lavoro associate all'artigianato e all'hobbistica, si colloca nella tradizione della "Appropriation Art”. I contributi di altre persone sono sempre esplicitamente il soggetto della sua arte. Per esempio, crea carte da parati dipinte a mano - una tecnica pre-moderna e quasi estinta - nei laboratori con bambini, che spesso si divertono particolarmente con i processi ripetitivi di creazione dei motivi. Il fatto che li paghi per il loro lavoro non va interpretato solo come un'espressione di apprezzamento, ma vuole anche sollevare la questione critica se il ritorno di una vecchia tecnica significhi anche il ritorno del lavoro minorile, di per sé superato. Anche i bambini vengono ormai completamente assoggettati alle logiche dell’economia?

Wiegard vuole aprire un dibattito su cosa potrebbe corrispondere meglio a un'idea di equità. Sarebbe forse più giusto non pagare i bambini, ma elencare i loro nomi nelle mostre con la carta da parati, onorandoli così come fieri/e collaboratori/trici? Oppure, non sarebbe meglio dare loro lo spazio per la libera sperimentazione con i materiali, in cambio del loro contributo nella produzione? Nel porsi sempre nuove domande da progetto in progetto e trovando sempre nuove risposte senza avere uno schema fisso con cui retribuire i/le partecipanti, rende ancora più presente il tema dell'"equità". A differenza di Santiago Sierra, ad esempio, che si limita a criticare le forme di remunerazione sfruttate, rendendo visibili le lamentele ma anche riproducendo, non senza problemi lo sfruttamento, Philip Wiegard crea i propri standard di cooperazione.

Il fatto che non sia affatto interessato solo a questioni di remunerazione diventa chiaro nei suoi lavori realizzati in FIMO, una pasta da modellazione popolare in vari ambienti di hobbistica. In questo caso, Wiegard utilizza un materiale tradizionalmente utilizzato per produrre lavori artigianali, finora lontano da qualsiasi "dignità artistica”. Nelle sue opere, include parti realizzate da persone che, proprio come i bambini, hanno uno status molto più basso rispetto agli artisti. Questo rende ancora più difficile raggiungere l'equità, l'equilibrio e l’uguaglianza.

Artisti come Roy Lichtenstein o Richard Prince, per la loro "Appropriation Art" utilizzavano estetiche similmente non artistiche, provenienti ad esempio da fumettisti o dalla scena motociclistica, erano ancora troppo orientati verso il gesto assolutistico dell'arte per pensare al giusto coinvolgimento degli autori del materiale del quale disponevano. Non chiedevano nemmeno l’autorizzazione per utilizzare i motivi. Se le persone interessate avanzavano richieste in seguito, rifiutavano qualsiasi riconoscimento. Apparentemente vedevano tutto ciò che era al di fuori e al di sotto il denominatore dell'arte come materiale di cui poter disporre a piacimento.

È probabile che il modo di lavorare di Philip Wiegard contribuisca ulteriormente a far sì che questo comportamento venga sempre più (dis)qualificato come arroganza e classismo. Per esempio, egli integra fin dall'inizio nei suoi processi di lavoro le star più o meno grandi della comunità FIMO, i cui motivi trova interessanti; chiarisce a quali condizioni può utilizzare il loro lavoro, propone modalità per dare loro una parte dei possibili ricavi e conclude persino accordi di prestito nel caso intenda esporre i loro oggetti. Ma questo non basta. Per Wiegard è importante non essere percepito come un conquistatore della scena creativa che decide in modo autocratico cosa gli piace, chi promuovere e chi escludere. Per questo ha iniziato a lavorare con il FIMO in prima persona; guardando tutorial per imparare dai professionisti e, dal momento in cui anche lui stesso è diventato un professionista, offre a sua volta tutorial in cui dimostra le sue tecniche e i suoi trucchi per trattare il materiale. Grazie a YouTube e TikTok, dove Wiegard pubblica i suoi corsi, è diventato una star tra i clayers: perfettamente integrato tra loro, non più un estraneo da risentire o da accusare di interessi biechi.

Il fatto che non solo prenda in adozione manufatti di persone appartenenti alla FIMO-community, ma che possa trasmettere la sua conoscenza delle tecniche per modellare questa pasta, gli apre ancora più possibilità. L'opera "Sunset Suites" (2021), ad esempio, consiste in una serie di immagini FIMO che un “Clayer” ha realizzato dopo un tutorial di Philip Wiegard e che mostrano l'uso creativo del motivo del sole al tramonto che ha appreso da lui. Quando Wiegard espone questi quadri, cambia ancora una volta ruolo e diventa un curatore che porta gli artisti all'attenzione del mondo dell'arte. Ma invece di limitarsi a conferire alle loro opere uno status esotico, come è consuetudine nella tradizione della "Appropriation Art", che permette al pubblico dell'arte di godere della propria presunta superiorità di gusto, fa di tutto per far sì che vengano apprezzate per le loro qualità formali, affinché siano percepite come un arricchimento per l'arte contemporanea.

Quanto Wiegard prenda sul serio questo aspetto è dimostrato anche dal fatto che per alcuni dei suoi quadri ha avviato una collaborazione con artisti della comunità del FIMO. I loro motivi o effetti, che ha appreso nei loro tutorial, diventano parte integrante e a volte persino visivamente dominante, dei suoi quadri. La loro paternità viene infatti specificatamente indicata nei dettagli del lavoro. In alcuni casi, in cui l'artista delimita chiaramente le loro parti dal resto della composizione, si potrebbe addirittura pensare che siano messi in scena in modo simile ai ritratti votivi nei dipinti medievali: come elementi di un'altra realtà, ma che rendono possibile il quadro in primo luogo e vengono ora apprezzati in esso.

In questo modo, l'etica della cooperazione nella pratica di Philip Wiegard non solo raggiunge un apice suggestivo, ma si manifesta anche nelle opere stesse. E quanto più quest'etica va oltre l'essere una mera questione procedurale sullo sfondo del lavoro artistico, tanto più chiaramente si contrappone alla spietatezza della modernità. Wiegard rappresenta in modo esemplare un nuovo tipo di artista, caratterizzato dall'intuizione che sia necessario restituire qualcosa alle persone o ai territori da cui si attinge. Allo stesso tempo, equità significa sostenibilità; infatti, l'etica della cooperazione segue un modo di pensare ecologico in cicli e contesti. Essere artisti oggi significa stabilire queste relazioni superando così rapporti unilaterali e ingiusti.

1/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

2/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

3/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

4/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

5/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

6/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

7/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)

8/10

Installation View, Philip Wiegard, "Dreams That Money Can Buy", 2023 Schloss Gandegg, Eppan/Appiano (Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo)